Brexit: how the end of Britain's empire led to rising inequality that helped Leave to victory

Danny Dorling, University of Oxford and Sally Tomlinson, University of Oxford

It was a man called Reginald Brabazon, Earl of Meath, who in 1903, two years after the death of Queen Victoria, suggested that her birthday, May 24, should be renamed Empire Day and become a day for patriotic celebration. His idea began to take off the following year and slowly spread in popularity. In 1909, Brabazon attended a day in Preston where a crowd of 20,000 people watched boys and girls parade past in what they were told was the national dress of each colony.

When World War I patriotic fervour was at its height, in 1916, the government gave in to calls for the day to be marked with an official state ceremony. But it wasn’t until the 1920s that the official celebrations really began to take off, and in May 1926, Empire Day became closely linked to the work of the newly established Empire Marketing Board. British school children all received a free mug and cake and were routinely taught that the British Empire was glorious. One woman, who grew up in Cardiff in the late 1950s, remembers being made to sing the following ditty at elementary school as the union jack was hoisted in the playground every Empire Day:

Brightly, brightly, sun of spring upon this happy day

Shine upon us as we sing this 24th of May

Shine upon our brothers too,

Far across the ocean blue,

As we raise our song of praise

On this our glorious Empire Day.

As the power of the British Empire waned after World War II, it became increasingly clear that Empire Day was done. In 1958, it was finally rebadged British Commonwealth Day, in 1966 merely Commonwealth Day. And in 1977 the date of the celebrations was moved to the second Monday of March where it remains today.

No doubt if Empire Day was still going, 2019 would have been a special year – marking the 200th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s birth. Still, long since support began to ebb away for formal celebrations of the British Empire, the echoes of empire have continued to reverberate in British political life. And as we argued in a recent book, Rule Britannia: From Brexit to the end of Empire, these echoes had a strong influence on why some of the 17.4m people who voted to Leave the European Union did so in June 2016.

The collapse of Britain’s empire in the decades after World War II was followed by a huge growth and the persistence of extreme economic inequality. Britain’s relative economic decline occurred in tandem with the loss of almost all of its remaining colonies in the 1970s and the economic benefit they had provided. The British thought that joining the European Economic Community in 1973 could replace this loss. It didn’t, because the European relationship was mutual, rather than exploitative.

At the same time, within Britain, inequality began to rise. Income inequalities rose from being among the lowest in Europe in the 1970s to being the highest of all 28 European Union member states by 2015, the year before the EU referendum. And the UK’s income inequality also saw the greatest rise during this period between 1976 and 2016.

Great inequality has damaged the lives of the majority of middle-class Conservative and UK Independence Party (UKIP) voters who live in the south of England. It damaged their lives because it hurt so many of their children and grandchildren’s life chances. Whereas their generation, when young adults, could more easily secure permanent housing, start a family, hold down a steady job and – if they were to secure a place – attend university for free, it’s primarily because of rising inequality that the next generations in England could not.

On top of that, states that tolerate greater economic inequality tend to experience less improvement in health and social services, which matter most as you age. This older group are far from being the poorest in Britain, but they are the large majority of people who voted Leave. They were told that the majority of their woes were caused by immigrants, which was untrue, but has been made all too easy to suggest. They know from their own pasts that something better is possible for them and they especially hope it will be for their grandchildren. And in June 2016, they were offered the chance to “take back control”.

This dynamic – the link between the end of empire and the rise of inequality in Britain – has not yet been given the weight of importance it should have in the analysis of the Leave vote. The scale of all the other empires of Europe, even when combined, pale in comparison to the British Empire, and its fall was by far the greatest of all.

Why the UK voted to Leave

Approaching three years after the referendum, no actual arrangements on leaving the EU have been agreed in parliament. The March 29, 2019 deadline came and went, with an extension to October 31. After months of disagreement, stalemate remains at Westminster.

There is still disagreement about who voted to leave the EU and why. Many accounts persist in suggesting that what swung the vote was disaffected working-class electors in the north of England, despite the majority of Leave votes coming from the south of England, from the middle classes and from people who normally vote Conservative or UKIP. What became clear by March 29 was how much the UK had descended into political disorder. Quarrelling, self-interested politicians, many of them demonstrably ignorant about their state’s imperial past, and fantasising about the future, were arguing about what sort of Brexit would suit their preferences and ambitions.

Some have claimed that the vote to Leave was the language of the unheard, a patriotic pro-sovereignty, anti-immigrant, anti-elitist movement. However, as Guardian journalist Anne Perkins recently noted, it was led by “millionaire, public school-educated financial traders, fronted by an Old Etonian [Boris]” in a “war room” organised by an Oxford-educated man – Dominic Cummings – who led the Vote Leave campaign.

Analysis of the largest referendum exit poll by the pollster Michael Ashcroft revealed that 59% of Leave voters were middle class. So was it the work of the poshest, the middle, or the poor? Who tapped into whose memories, dreams and prejudices most effectively to secure a Leave majority, and why?

In the aftermath of the referendum result, almost every political party and campaign group want to claim that its view on what should happen next represents the real “will of the people”. They often especially wish to co-opt the support of the downtrodden working class and the unheard majority in the north of England to their cause. Yet, Leave voters were marginally more likely to live in the south of England, and three-fifths were middle class. Still, those who voted Leave did have one clear trait in common: they were mostly older, English voters, many of whom are likely to remember Empire Day.

What’s been lost

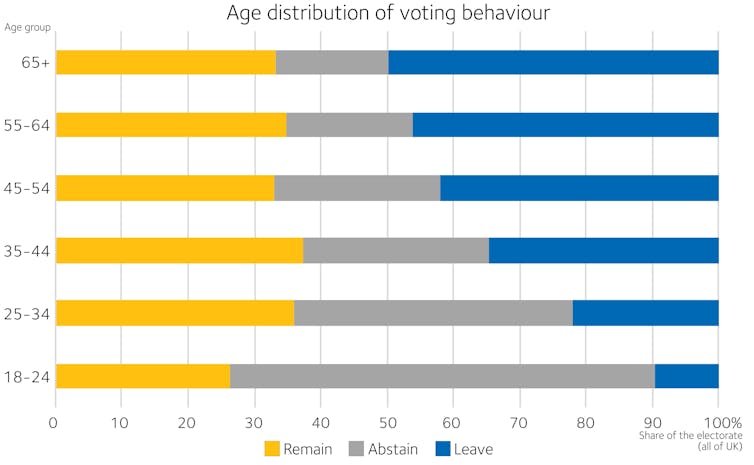

Age was the most important factor in the Brexit decision, with a majority of those over 45 voting to leave, rising to more than 60% of those aged over 65. Incidentally, people aged over 90 – old enough to clearly remember World War II – tended to be very pro-Remain, but their numbers are now inevitably small.

This older generation lived through the era of full male employment between 1945 and 1976, and the greatest rises in standards of living for all up until 1976 – and they then watched as this was lost between 1976 and 1986. This feeling of loss continues today. As the former Labour minister, Alan Milburn, explained in his December 2017 letter of resignation as chair of the government’s Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission:

Whole communities and parts of Britain are being left behind economically and hollowed out socially. The growing sense that we have become an us and them society is deeply corrosive of our cohesion as a nation.

Empire rhetoric and thinking was used to deflect the anger of the majority towards others – others always painted as inferior to them, especially migrants. As Philip Murphy, director of the Institute for Commonwealth Studies, argued in 2018: “Eurosceptics, currently in the ascendant are implicitly rehabilitating the racialised, early 20th-century notion of the Commonwealth as a cosy and exclusive Anglo-Saxon club.” Those who had taken the most, who had grown rich from empire while the majority of the population of Britain saw their living standards stagnate, often did so on the back of a little “family money” from the past.

It is now time to fully recognise that as the opportunities of empire faded, a small group of those with a little financial advantage at home, began instead to exploit their fellow British citizens for more and more profit. The take of shareholders in British companies began to rise and the wages of British workers didn’t keep pace.

Unlike in the US, where real median wages were virtually static at this time, median wages did rise in real terms in Britain in the 80s and 90s, but they didn’t keep up with shareholder dividends. Wages at the top also rose far faster than those at the bottom. This was the story of the 1980s and 1990s.

Tactics of divide and rule, and breaking dissent that had been applied overseas to different groups in different ways were now aimed at British trade unions, British activists and agitators, and British politicians who argued for greater equality. Divisions rose, poverty spread and unemployment was called a price worth paying in the 1990s.

Fast forward to 2014 and falling national life expectancy in the UK has been treated as mere collateral damage. The countries of the UK cannot afford a decent health service, their people were told, because too much money was being sent to Brussels. And again, they needed to “take back control”.

The politics of austerity, introduced in 2010, have led directly to the proliferation of urgently needed food banks and the cuts in social and health services which also contributed to rising infant mortality in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Nowhere else in Europe were more babies dying each year as infant mortality rates rose. The worst effects of inequality and austerity were felt in the north and by the poor.

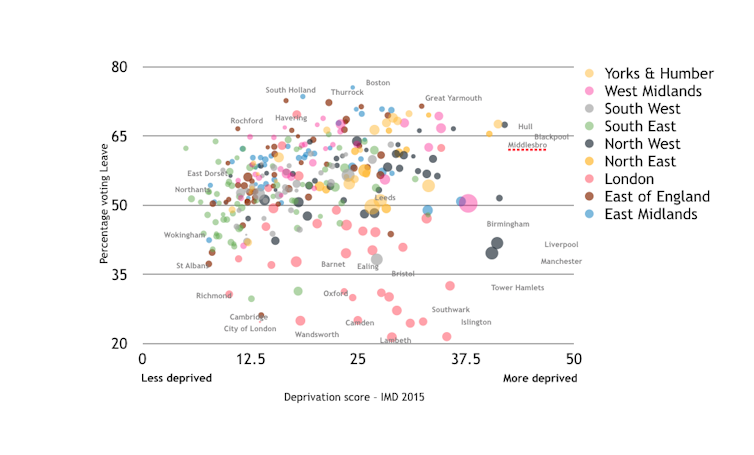

Despite this suffering, it wasn’t poverty and deprivation in northern areas that caused people to vote to leave the EU. Our own careful study of the geography of the vote included in our recent book, coupled with polling evidence, makes clear that it was older, less well-off Conservative voters in both the north and south who swung the vote, and there were far more of these in the south of England where they also turned out to vote in the referendum at a higher rate. This is why the greatest absolute numbers of Leave voters were in the south of England.

Overall, 52% of people voting Leave in all of the UK lived in the southern half of England – home to a minority of the UK electorate – and a majority of these Leave voters were in the middle classes. At a local authority district level, there was essentially no correlation between voting Leave and deprivation, which shows that the driving force behind the vote to Leave was not being left behind other areas.

Back in control

In 2012, the broadcaster Jeremy Paxman suggested that even when the colonial administrator and his home counties wife had long given up their gin sundowners on the veranda, the native British had been cushioned from reality because the empire gave a comforting illusion about their place in the world and “a stupid sense they were born to rule”.

Added into this mix, the “take back control” slogan employed by Leave campaigners was a very powerful message. It harks back to when the British actually had a lot of control. Older people, the grandparents of today, “knew” without thinking about it that up to 1947 Britain was in control of some 700m people in an empire stretching around the world and most of them thought that this was a “good thing”.

Yet questions about whether the empire was good or bad miss the point that it was largely because of the loss of such a huge empire, and the loss of the expropriation of its wealth and labour power, that economic inequality in Britain has risen so rapidly.

Britain’s industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the claim to be the workshop of the world, was fuelled by raw materials dependent on slave and indentured labour overseas. It was built around the concept of “free trade” that opened up foreign markets for Britain under the watchful eye of the gunboat and ensured global economic control in case others tried to muscle in on that free trade.

The British grip gradually disappeared during the 20th century, the pound relentlessly fell against the dollar across that century, and many of the British wealthy blamed the labour movement and eventually the EU for their diminished status in the world. They rarely saw their family riches as unfairly won in the first place.

The loss of India in 1947 and most African colonies in the 1960s had effects that were felt most keenly decades later. It wasn’t long after the colonial investments of the wealthy first turned sour that Conservative governments in the early 1980s began to cut taxes for the wealthy at home and pulled the plug on poorer regions. This plug was pulled in many ways, from ending the regional funding of poorer areas that had begun with the Special Areas Act of 1934, through to state support of industries and infrastructure in the south-east of England and especially London.

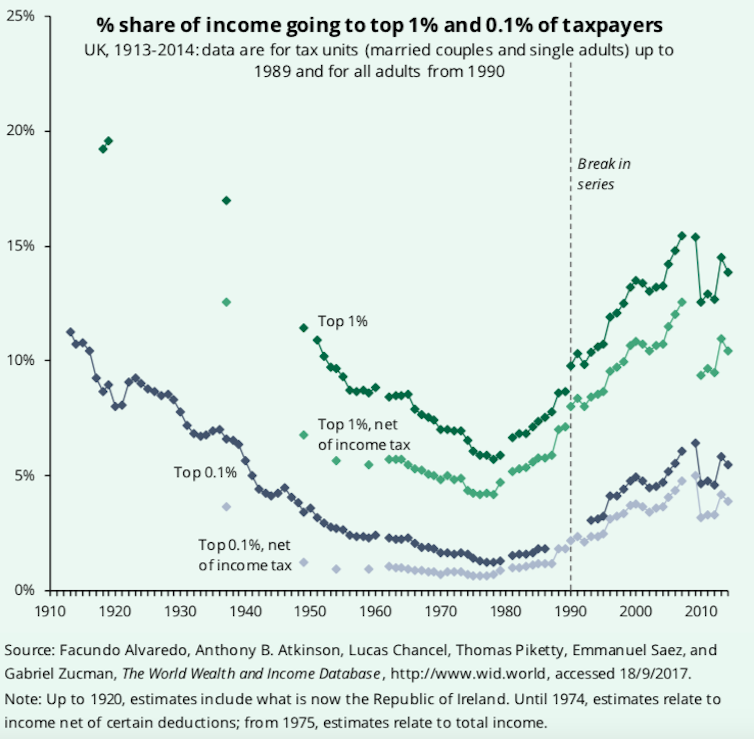

The rich British became poorer when the empire disappeared. The evidence is clear to see in graphs that track the falling take of the top 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% of UK taxpayers.

The fall in the fortunes of the very wealthiest had actually begun earlier, after the end of World War I. As the author Evelyn Waugh wrote in Brideshead Revisited, of the fictional Marchmain and Flyte families: “Well they are rich in the way people are who just let their money sit quietly. Every one of that sort is poorer than they were in 1914.”

In 1913, the richest 0.01% of households in the UK received 425 times the average household income per year. By 1976 that had fallen to just 30 times. But by 2014 it had risen to 125 times. Figures for very recent years are yet to be released by the government.

In 2018, the inequality gap between the richest and poorest in Britain, by income was at a post-World War II peak. The best-paid 10% of households were each on average receiving almost three times as much per year as the median household. Yet inequality has still not regained its 1913, pre-war peak. It is a long way from that and to get there would require a remarkable further dislocation of British society.

Increasing xenophobia

The British public have been distracted from this rise in inequality and absolute poverty by suggestions that immigration was, and continues to be, the main cause of their many problems. Newspaper owners, some immigrant themselves, encouraged the vilification of immigrants, with the UK prime minister, Theresa May, repeatedly claiming that if immigration was reduced to the “tens of thousands” then all would be well. In the ten weeks before the Brexit vote, more than 1,400 articles in the popular press mentioned immigration.

The patriotic songs sung annually at the last night of the proms in London are part of a myth-making of the nation. Rule Britannia may claim that Britain “never never never” shall be slaves, but the story the song tells overlooks the realities that Britons were slaves to the Romans, Vikings, Danes, and Normans, and that the royal family is descended from the French, the Dutch and the Germans.

As they invaded countries around the world in imperial expansion, the British saw themselves as traders, lawmakers, administrators, missionaries – but never as immigrants. It has taken a long time for the British to adjust to their loss of territories and imperial subjects, and many have never adjusted to the entry of others into the UK, even if imperial subjects were also encouraged to regard it as their “mother country”.

Until the latter part of the 19th century, rich or aspirant foreigners were tolerated, such as German mill owner Frederick Engels and his author friend Karl Marx, and also the young Michael Marks and his friend Thomas Spencer who opened a market stall in Leeds. But in 1893, a magazine – ironically called “Truth” – described immigrants and foreigners as: “Deceitful, effeminate, irreligious, immoral, unclean and unwholesome.” Such comments were rare at the time but became more and more common as scapegoating migrants for the harm caused by rising poverty and inequality in Britain grew in popularity.

The Daily Express and many other newspapers began to print increasingly xenophobic material from the turn of the 20th century. It was then unthinkable that those regarded as “black and brown inferiors” would come to Britain to settle. At first, in an uncanny echo of today, it was Eastern Europeans who were most feared. The 1905 Aliens Act gave the home secretary responsibility for immigration and nationality. It was mainly designed to prevent Jewish immigration, and was supported by an organisation called the British Brothers League which aimed to: “Stop Britain being a dumping ground for the scum of Europe.”

All this goes to show that neither anti-immigrant and anti-European sentiment, nor legislation to control immigration, is new to Britain. Some 14 immigration control acts and other controls were passed in the later 20th and early 21st century, making nonsense of claims that only after Brexit can the country “take back control” of its borders. The obsession with control has been going on for decades, a further immigration control bill is currently before the British parliament and the Home Office is planning an “immigration status” database, a development that has been met with alarm by human rights groups.

The events surrounding the Brexit vote also resulted in a huge surge in hostility towards racial and ethnic minority groups, migrant workers, and refugees. This hostility is a continuation of past ideologies: race and empire have shaped the concept of British national citizenship and thinking as to who should be included or excluded.

Taught to feel superior

Older people – who were the driving force behind the Leave vote – have had much more experience of a more overt ethnocentric, jingoistic school curriculum. The high point of empire, from the late 1880s onwards, coincided with the development of mass elementary education. A value system, based on military patriotism, xenophobia, racism and a nationalism that excluded foreigners, filtered down from the upper-class public schools to the middle-class grammar schools and into the elementary schools for the working classes.

Those young men who ran the empire had to feel effortlessly superior to the populations they were sent abroad to govern. The working classes had to be helped to feel superior. To one boy brought up in a Salford slum in the early 20th century: “School was a blackened gaunt building, made exciting by learning that there seemed to be five oceans and five continents, most of which seemed to belong to us.”

The working class were encouraged to ignore their poverty in the belief that they were superior to the natives overseas. The 1880s to the 1930s was a time when vast areas of Asia and Africa were being invaded and taken over by the British, and a range of invented imperial traditions were developing. A passion for classification of supposed classes and races on biological and eugenic lines was developing alongside stereotypes of the ignorant and deficient working classes, similar to those tropes of superiority over the stupid and lazy natives overseas.

Into the 1960s, maps on classroom walls had large areas coloured pink, which illustrated the colonies belonging to “us”, and into the 20th century, school textbooks, juvenile literature, and films extolled the adventures of those imperial adventurers who had made Britain Great. As the historian John Bratton noted:

England was presented as a gallant little nation, whose power and conquests are the rewards of merit, since all opponents are bigger and uglier than she is.

Part of the importance of understanding imperial education, and its modern-day significance, is that many of the most senior Conservative party politicians were educated in private schools in decades when unreconstructed imperialism was still a part of the curriculum. A textbook still in use in Sussex schools in the 70s described the races of mankind as the Caucasian or white race, the Mongoloid or yellow race and the Negro race.

The British school system continues to produce young people who, upon becoming university students in 2017, felt it appropriate to chant outside a black student’s room at Nottingham Trent University “we hate the blacks” and “sign the Brexit papers”. There are many other contemporary examples of racist behaviour by university students in Britain today, which has its roots in the days of empire. What matters is to understand the environment that helped and continues to help such ignorance to grow.

Sinking in

The Brexit campaign was a useful diversion from growing economic inequality in Britain and the lack of any plan to address this great injustice. But the realities of leaving the EU are beginning to sink in. What meagre economic growth occurred before the referendum and post 2008 has been lost. Wages have not kept up with inflation – they have only outstripped inflation for brief periods and only for a few months at a time.

There is now growing inequality in the UK’s already terribly divided school education system as a result of cuts to state school funding – a real terms cut since 2015 of £5.4 billion. The health service is struggling as real costs far outstrip any funding increases, and a housing crisis led to a threefold to tenfold rise in the numbers of people sleeping on the streets between 2010 and 2018. The latest official figures suggest the number of people sleeping rough in England fell by 74 between 2017 and 2018. The huge real increase resulted in a rise in numbers found dead.

More people are at work in the UK, as the population has increased. More women, older, and disabled people have been encouraged or coerced to work, but the jobs are low paid and exploitative. The most recent data from the Office for National Statistics shows that pay growth is slowing and that incomes of the poorest fifth are down by 1.6%. Meanwhile, the incomes of the richest fifth rose by 4.7% in the 2018 financial year.

Income inequality is rising, and wealth inequality is staggering. Child poverty was reported – on BBC children’s TV – as having become the new normal in many parts of Britain.

Amid all this, and in an effort to put a positive spin on post-Brexit Britain, in September 2018, Theresa May announced plans for a Festival of Britain to begin in 2022. The prime minister said that the festival would aim to “showcase what makes our country great”. And it was reported that this new festival would cost an estimated £120m to prepare. In April 2019, the think tank British Future pointed out that “holding a Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 2022, on the centenary of Ireland’s partition and civil war, would be the worst possible timing”.

No Festival of Brexit will compensate for the rise in inequality across the UK. But the country could use such an event to help teach people something they really need to remember from their past. Children were once told at school that the reason the British were so rich was because its people were special. That was not the truth. They were so rich because they sat at the heart of the largest empire the world has ever known and benefited hugely economically from that.

Being a member of the EU was not the cause of the UK’s woes, neither was immigration. If the British really want to take back the control they will need to reassess their more recent history. Knowledge is power.

Education and Race from Empire to Brexit.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford and Sally Tomlinson, Emeritus Professor at Goldsmiths, University of London and Honorary Fellow, University of Oxford

Comments

Post a Comment