Banning zero hours contracts would help reduce the gender pay gap

Ernestine Gheyoh Ndzi, University of Hertfordshire

The gender pay gap has been around for as long as woman have been in the workforce. No matter the reasons that get put forward as to why men get paid more than women, it generally comes back to the fact that women take on more child rearing and caring responsibilities than men.

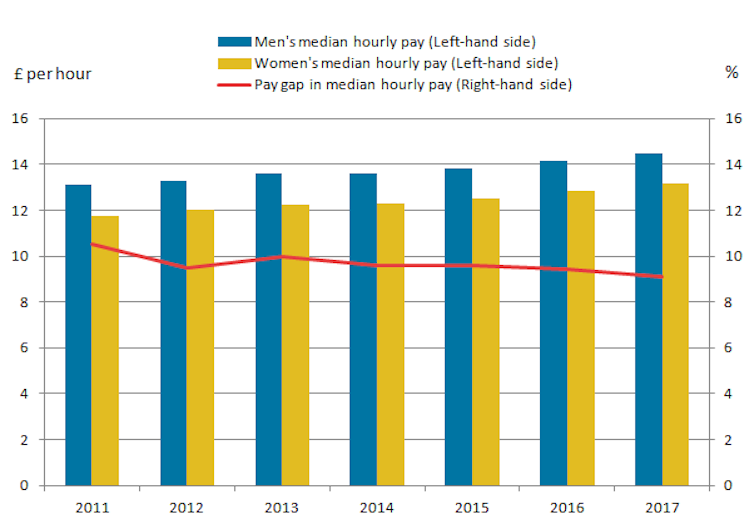

The gender pay gap in the UK stands at 18.4% in favour of men for full-time and part-time workers, according to the Office for National Statistics. But what the ONS fails to account for is the number of women on zero hours contracts. If it did, the gender pay gap would be even worse for women.

Gender pay gap regulation, introduced in 2017 requires companies that employ 250 employees or more to publish annual gender pay levels in their organisations. But zero hours contract workers are not considered as employees under the law. This means that those on zero hours contracts – a group of which women make up a bigger share – are left out of the official gender pay gap report.

The ONS report and analysis on the gender pay gap were only able to account for 36.1% of the difference in men and women’s pay – leaving a significant percentage unexplained. It is possible that the number of women on zero hours contracts could go some way to accounting for this.

The Equality Act 2010 makes provision for men and women doing equal work to be paid the same and also includes an equality clause for every contract of employment. But again – because this doesn’t include zero hours contracts, which are increasingly being used and which disproportionately affect women – the Act has limited power to improve the gender pay gap.

Zero hours contracts are common in sectors described as “feminine” – including the accommodation and food industry, health and social work, retail and hospitality. In sectors that are considered to be male dominated, such as technology, there is little to no evidence of the use of zero hours contracts.

Lack of alternatives

Research by sociologists at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge demonstrates that a number of people are on flexible contracts for lack of alternatives – not out of choice, as is often alleged by employers who use them. Women in particular look for flexible work to fit around childcare, school and other caring commitments – and this is often insecure and unpredictable because of the nature of zero hours contracts.

The Taylor Review of modern working practices has confirmed that too many employers still rely on these contracts. Though widely applauded for their flexibility, they rarely bring out what people like about flexibility.

In an ideal world, flexibility of employment would give workers greater control over the hours they work, enabling them to fit it around child care, studies and other commitments. But the flexibility that comes with zero hours contracts tends to favour employers, who exercise their control over an insecure but willing workforce.

Thus, zero hours contracts are generally known for poor pay and working conditions, which diminish workers’ morale and productivity. They transfer business risks away from employers and onto workers.

The fear of being fired or not offered any work forces those on zero hours contracts to take the low pay they are offered and endure the poor working conditions in exchange for any flexibility the contracts offer. One study by The Fawcett Society, a women’s lobby, found that 14% of women on the lowest pay were on zero hours contracts. Plus, 40% of the women were on zero hours contracts because that was the only job they could find, and 61% of the women felt they could not turn down work for the fear of not being given work subsequently.

To remedy this issue, the Taylor Review recommended that businesses that want to employ people on zero hours contracts must pay for the privilege by applying a higher minimum wage to non-guaranteed hours. This is disappointing. It fails to consider the gender consequences of zero hours contracts, even though it acknowledged that the practice was common in female dominated sectors.

If the government’s Low Pay Commission implements this higher pay recommendation, the difficulty will be how it will work in reality. After all, employers have demonstrated that they are capable of paying zero hours workers below the national minimum wage.

Ernestine Gheyoh Ndzi, Senior Lecturer & Cohort Tutor, Hertfordshire Law School, University of Hertfordshire

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Comments

Post a Comment