Poor people are penalised for borrowing to make ends meet – a new alliance gives them another way

Karen Rowlingson, University of Birmingham

Michael Sheen has just launched the End High Cost Credit Alliance. The actor has supported various charitable causes over the years and is now leading this effort to support alternatives to high cost credit which has increased in recent years, not least in his home town of Port Talbot.

The alliance was formed in response to the fact that those on the lowest incomes pay the most to borrow money even where they are borrowing for essentials. This is compared to those on higher incomes who can generally borrow at lower rates for luxuries like holidays and high-end consumer goods.

The alliance aims to debate the changes needed to deliver healthy credit, offer solutions, and provide the resources to test them out locally and at scale across the UK. It also collectively calls for changes to policy, regulation and practices to make credit fairer for all.

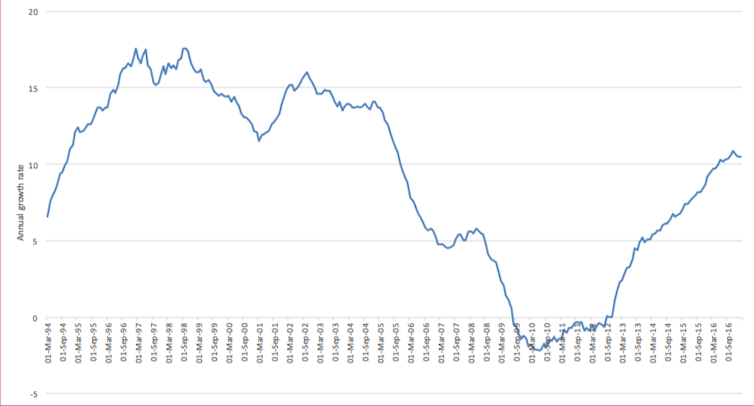

This is a growing problem. Research by colleagues and myself at the Centre for Household Assets and Savings Management at the University of Birmingham has shown a massive increase in lending over recent years. Our latest financial inclusion monitoring report shows that credit card lending is now at a higher level than at the peak of the financial crisis in 2008.

Consumer credit (excluding credit cards) also increased massively after 2010, with much of this likely accounted for by car finance. And the very latest figures appear to show this growth in lending tailing off, though it remains much higher than in 2008.

Alternative lenders

But those on the lowest incomes are much less likely to borrow on credit cards or get personal loans for new cars. Instead, they turn to alternative lenders such as payday lenders, rent-to-own and home collected or doorstep lenders. And often this is to pay for basic items such as school uniforms, nappies, white goods and sometimes even food, and to tide them over between jobs. Or when their wages are lower than expected due to zero hour contracts and casual work.

These alternative lenders typically charge far higher rates of interest than mainstream lenders. For example, in 2016 the charity Church Action on Poverty highlighted the cost of buying a fridge freezer from BrightHouse, a large weekly payment retailer with shops on many local high streets. The total cost was £1,326, which included the purchase price of £478.33, interest of £658.74 and various warranty and delivery charges. The exact same fridge freezer, bought through Fair For You, a not-for-profit Community Interest Company, would have cost a total of £583.68 (including the purchase price £373.99 and interest £120.38).

According to the Financial Conduct Authority, 200,000 people took out a rent-to-own product in 2016 and 400,000 had outstanding rent-to-own debt at the end of 2016. The home-collected credit market is larger, with 700,000 people taking out a home-collected credit loan in 2016 and 1.6m people with outstanding debt on these products at the end of 2016.

So it is clear that hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people on low incomes are paying dearly for access to credit. But this need not be the case if the market is appropriately regulated and alternatives are supported.

The need for regulation

In the last few years stronger regulation of high cost credit has been introduced. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) regulator introduced a series of reforms in 2014-15 to tackle irresponsible lending, including a price cap on high-cost short-term credit, which has helped to reduce the cost of payday lending. Then, in October 2017, BrightHouse was ordered to repay £14.8m to nearly 250,000 customers after the FCA found it had not properly assessed a customer’s ability to repay – and they would now be compensated.

So far so good. But the FCA’s price cap only applies to certain kinds of credit (particularly payday lending) and this means that other forms of high-cost credit such as home collected credit and rent-to-own are excluded from the cap. These forms continue to charge extremely high levels of interest (alongside other charges in the case of rent-to-own). Plus, mainstream sources of credit such as overdrafts and credit cards are also excluded from the cap, even though they can work out to be just as expensive as alternative sources of credit.

The FCA is currently considering further ways to tackle high cost credit and our research chimes with a 2017 report from the House of Lords Select Committee on Financial Exclusion, which recommended far stronger regulation of consumer credit along with further support for credit unions and microfinance institutions.

As well as strengthening the regulation of high cost credit, it is also important to support alternatives such as the not-for-profit Fair For You initiative. Credit unions are another alternative to high-cost lenders, supporting their members to save, borrow and gain access to other financial services. They are financial co-operatives, owned and controlled by the members.

Our research also highlights that many people in the UK, both in and out of work, are on very low incomes which vary week to week. This makes it very difficult to make ends meet and is one of the main reasons why people turn to credit. It is therefore important to tackle these fundamental problems of poverty and precarity, as well as the issue of high cost credit.

Karen Rowlingson, Professor of Social Policy, University of Birmingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Comments

Post a Comment