Brexit will hit Britain's overseas territories hard – why is no one talking about it?

Paul Hare, Heriot-Watt University

When the Brexit referendum result was announced last June, I was working on the Turks and Caicos Islands, one of the UK’s overseas territories in the Caribbean. A collection of about 40 tropical islands, of which eight are inhabited, people there were shocked at the result. They were annoyed they hadn’t had a chance to vote, and concerned about their future.

It was all too apparent that neither side in the campaign had given serious thought to the implications for territories like this one, and the situation has not improved since then. There are genuine and serious concerns that need to move up the agenda.

The 14 British Overseas Territories (OTs) are remnants of empire, mainly scattered through the tropics. An exception is Gibraltar, the only territory that is also part of the EU. It is facing well documented issues such as a possible closed border with neighbouring Spain and losing the right to provide services such as finance and online gambling to the rest of the EU.

The remainder of the territories are mostly further afield and receive much less attention in the UK media. Besides the three without civilian populations – British Antarctic Territory, British Indian Ocean Territory and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands – the rest have varying reasons to be nervous.

In the Caribbean, the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands both do well from specialist financial and business services – as does Bermuda to the north. They are therefore most likely to be affected if Brexit reduces the UK’s influence in determining the prevailing international rules and regulations that govern these activities – with the EU one of the key players here, this is a distinct possibility.

Fund management

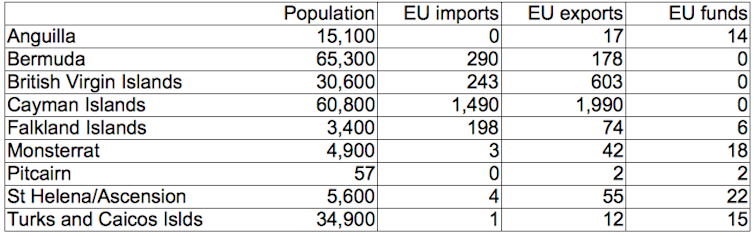

Of the three other Caribbean territories, Anguilla and the Turks and Caicos Islands have successful tourism sectors, while Montserrat is still struggling to recover from major volcanic eruptions two decades ago. Yet each relies to a greater or lesser extent on EU aid programmes that provide support to all but the richest of the OTs of EU member states. (Strictly speaking the funding is outwith the main EU budget, but the EU manages the money through its International Development and Cooperation Directorate.)

Brexit implies that the current aid programmes will probably be the last for these and the other OTs – they will not be eligible when the next round of contracts comes on stream from 2021. This comes at a time when Anguilla, the Turks and Caicos Islands and also the British Virgin Islands all need “significant reconstruction funds” to make up for recent devastation from Hurricane Irma.

Elsewhere, losing EU funding will hit some and not others. Bermuda is rich enough not to get EU money, but they do have similar concerns to the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands about banking and financial market regulation.

The Falklands, on the other hand, look like being among the losers. They can probably just about manage – depending on what happens to the fishing licences they currently sell. These mostly go to Spanish ships, who are partly attracted by the Falklands’ current tariff-free trade with the EU. This situation might depend on the post-Brexit fisheries regime.

Funding looks precarious for the islands of St Helena and Ascension, off the coast of Angola. St Helena is already experiencing unwelcome publicity over the recent completion by the UK of an airport in a place too windy for planes to land, though at least they may now be making it viable. Also threatened is the tiny island of Pitcairn, home to the Bounty mutineers in the south Pacific. With barely 50 inhabitants, funding cuts could put pressure on the islanders to leave.

Earlier this month, the House of Lords EU Committee wrote to the Brexit secretary, David Davis, seeking assurances that it might replace any of this “lost” EU funding, but so far none have been forthcoming. With continuing pressure on the UK public finances, and some critical media commentary about the UK’s international development aid programmes, it is hard to be confident that new funding will emerge.

Trade troubles

The Caribbean territories in particular could also face trading issues, since there is an EU frontier in the region. This arises because several French Caribbean territories including Guadeloupe and Martinique are legally part of France proper and not self-governing, and are therefore part of the EU.

The extent to which this will cause problems in practice varies. For Monsterrat, its exports to Guadeloupe should be unaffected, for example, since Monsterrat is a full member of Caribbean trading bloc CARICOM and a party to the EU-CARICOM trade partnership. Anguilla, on the other hand, is potentially more complicated. Anguilla is not a party to EU-CARICOM and it is not clear how its future trade with French overseas territories will be managed.

The issues are a bit like those affecting Northern Ireland and its future relations with the Republic of Ireland. Hopefully, solutions can be found that facilitate normal trade and commercial links without erecting new barriers. More generally, the OTs currently enjoy tariff-free trade with the EU – depending on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, this too could come to an end.

The overseas territories are diverse places that are proud of their British heritage and sense of identity. They have been remarkably loyal to the UK and are keen to keep up their links, but also expect to be looked after as if they were part of the UK proper.

Paul Hare, Professor Emeritus, Heriot-Watt University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments

Post a Comment